Whether public or private, primary, middle or secondary, schools generally run on a tight schedule on even tighter budgets. These parameters are often unyielding, which means that communicating your concerns from your perspective as a Spanish teacher to your higher-ups can sometimes be a nerve-wracking experience.

For example, we recently received this message from one of our teachers here at SpeakingLatino:

“Our school is getting ready to set up the class schedule for next year. The principal asked for our input, and then told me that my input didn’t really matter because I don’t teach a ‘core class.’ She basically told me that Spanish would get the leftovers of whatever the schedule could accommodate.”

We imagine that many Spanish teachers have received messages like this one, either as direct as this message or even something more subtle. Receiving this kind of feedback can feel demoralizing, as the sense of being somehow ‘less than’ despite your role as a full faculty member is surely disorienting.

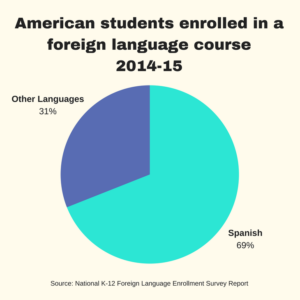

To make matters worse, in some situations, the learning of Spanish, and therefore the teaching of Spanish, is under-appreciated in a general sense as well as a scheduling sense. Even though the National K-12 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report states that, of the students enrolled in a foreign language course in the academic year 2014-15, 69% of American students studied Spanish (and the next highest percentage studied French at 12%) negativity persists in some schools.

To make matters worse, in some situations, the learning of Spanish, and therefore the teaching of Spanish, is under-appreciated in a general sense as well as a scheduling sense. Even though the National K-12 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report states that, of the students enrolled in a foreign language course in the academic year 2014-15, 69% of American students studied Spanish (and the next highest percentage studied French at 12%) negativity persists in some schools.

But why is the relevance of Spanish so often questioned, despite the growing population of Spanish-speakers and the countless benefits of learning another language?

It’s hard to say why Spanish is regarded in this way. Is it too practical, and therefore less of an intellectual pursuit than Latin or French? Is it tied up in political opinions around immigration? Is it too familiar, and therefore suffering from the crisis of predictability that rarely impacts other more exotic choices like German, Japanese and Mandarin?

To complicate matters even further, only a percentage of American students even have access to the study of a foreign language. This phenomenon as well as the questions around relevancy all speak to why it is unlikely that Spanish will ever become a core class like math or English.

So how can you talk with your administrators about these kinds of concerns? We did some research to find out.

An Administrator’s perspective

We spoke with Kevin K., an administrator with 18 years of experience building schedules. He confirmed what we all already know: Spanish is not a core class, so expecting it to be treated as such is unrealistic. Simply put, Spanish is not subject to the considerations that impact core classes like math and English.

Kevin did, however, point out that though administrators are under pressure to put the interests of core classes ahead of those that relate to electives and optional classes, this does not mean that teachers of Spanish are voiceless.

Kevin suggested that Spanish teachers explain to their higher-ups that they feel a responsibility to advocate for the content they feel strongly about. He pointed out an important detail: if Spanish teachers don’t speak up for their own programming, then who will? Sometimes, fresh ideas come from perspectives different from those of administrators, so Spanish teachers who present their ideas thoughtfully may be able to offer administrators a valuable point of view.

He also offers educators one important caveat: teachers need to remember that ultimately, administrators are the ones who are responsible for the schedule. All teachers can do is provide ideas and hope for the best. After all, everyone, even administrators, are doing the best they can within strict boundaries determined by someone else, like the state government or the board of the school.

Your overall contribution to the school reflects well on your Spanish program

Next, we found that, Anne Marie, the Spanish teacher blogger behind MrsSpanish.com, has some interesting and helpful observations about conversations with administrators. She asserts:

“I don’t think there is a magical article you can give them or a magical conversation that will suddenly change a difficult administrator’s mind about the worth of your program. Honestly, it comes down to your contribution to the overall big picture of the whole school. It is about building a relationship with your administrator.”

Anne Marie goes on to explain that administrators are under constant pressure, especially as standardized testing is such a powerful factor impacting budgets, jobs, school reputations and everyone involved in that school’s community. She adds, “Hopefully you can get an administrator that can see the difference in ‘what the state wants to see’ and ‘what is best for students’ because many times those two are NOT the same.”

Anne Marie also offers relationship-building tips to help teachers develop a rapport with their administrators. Anything teachers can do to show administrators they have the well-being of the school community in mind will serve them well: “You show up on time, and you don’t jet off right after school. You turn in paperwork, you volunteer for committees, you participate in faculty meeting, and you are a team player. When your administrator comes to observe you, know what they are looking for and help them ‘check all the boxes.’”

Anne Marie also offers relationship-building tips to help teachers develop a rapport with their administrators. Anything teachers can do to show administrators they have the well-being of the school community in mind will serve them well: “You show up on time, and you don’t jet off right after school. You turn in paperwork, you volunteer for committees, you participate in faculty meeting, and you are a team player. When your administrator comes to observe you, know what they are looking for and help them ‘check all the boxes.’”

All of these efforts show administrators that teachers are trying hard to do what’s best for the school and the students at large. She points out that the inevitably successful results of such hard work have the added bonus of promoting the Spanish program and the teachers involved. Bringing positive attention to your work and to your students’ progress can only help matters when you need to bring a concern the attention of your administrators.

Remember to consider what helps the school overall

Finally, Amy Lenord, another teacher-blogger with extensive experience to share, reminded us that administrators and teachers just see things differently. She does not recommend confronting administrators directly with concerns around administrative policies surrounding non-core classes; instead, she encourages teachers to think and to act in terms of what will bring prestige to the school as a whole as a way to market themselves and their good work.

Motivating students to learn so that test scores reflect progress is one example of how Spanish teachers can re-focus their energies, as well as engaging students with innovative programming. According to Lenord, inviting administrators to observe student success in action is a much more positive and efficient way to effect change and to demonstrate the importance of Spanish education.

Understanding “The Big Picture” is the key to success

So perhaps it might be worthwhile to invest some time in understanding the state of affairs at your school. Learn about your school’s attitudes towards the teaching of Spanish in order to develop your own expectations around what is realistically possible. Remember that all three of our commentors suggest thinking in terms of the big picture when you are presented with a less-than-ideal scheduling situation.

Perhaps, the true answers lie within; instead of worrying about how your teaching and your program are perceived by others, invest the emotional energy in making your Spanish class the most engaging and successful one you can. The results will speak for themselves. And though progress and change might feel slow, you will know that the most important people in your teaching life are getting the most out of you and your efforts: not your administrators, after all, but your students.

Take a look at our article The Right Way To Approach Your School Administrator.